THEY KNEW AND DID NOTHING

BY HENRY-LOUIS TAYLOR, JR. | BETH KWIATEK | IAN STERN

A flood of news articles, magazine essays, and Twitter commentary, including from The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Washington Post, the Atlantic, the Guardian, and others, have appeared since late March on race and the coronavirus. They all report or comment on the disparate and inequitable impact that COVID-19 is having on African Americans, people of color, and immigrant communities. They are writing as if to sound the alarm that COVID-19 is a ticking racial time bomb, challenging the old mantras that this virus is “equal opportunity.” These pundits are learning that this is not true and are attempting to explain why black and brown people are particularly vulnerable to the virus. These essays all argue that COVID-19 has exposed the fault lines of systemic structural racism in the United States. And, more importantly, the failure to act can have deadly consequences for Black America.

COVID-19 arrived on U.S. soil in late January 2020. No one ringed the alarm for Black America. Now, the coronavirus is raging like a Tsunami through black communities across the country. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that illness caused by the coronavirus is disproportionately affecting African Americans. In Chicago, blacks comprise 30% of the population but make up 70% of COVID-19 deaths. In Milwaukee County, blacks account for 81% of the deaths but constitute only 27% of the population. In Louisiana, blacks comprise 33% of the population but account for 77% of those who died from COVID-19. Similar realities exist in Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., Buffalo, Atlanta, and other cities with large black populations.

These numbers are ever-changing, and the data is still incomplete, but the emerging pattern shows that nationally blacks are being infected and dying at a disproportionally high rate. The devastation of African Americans by this virus did not have to happen. It was no fait accompli. Black vulnerability to disease was ignored, overlooked, and dismissed.

The White House, elected officials, physicians, and public health experts must have known that COVID-19 would hunt and kill African Americans in disproportionate numbers. How could they not? Thirty-five years ago, in 1985, Margaret Heckler, a Republican, and then Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in the Ronald Regan administration, released the Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health. This landmark study documented the existence of significant race-based health inequities. It concluded that such health disparities are “an affront to both our ideals and to the ongoing genius of American Medicine.”

“THESE CHRONIC

ILLNESSES ARE

COMMODITIES

ASSOCIATED WITH

COVID-19.”

Since the release of the Heckler Report, the nation has spent billions on research related to race-based health inequities. Concurrently, health activists transformed public health by theorizing on the role of social determinants in the production of undesirable health outcomes. Then, in 2001, to advance research on blacks and people of color, the National Institutes of Health established the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to improve minority health and eliminate health disparities.

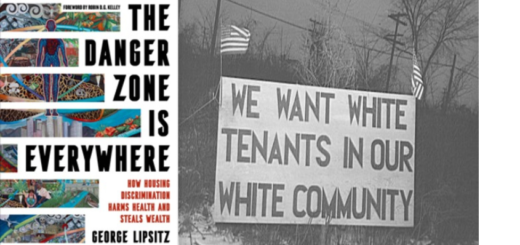

Thirty-five years of research, then, have chronicled the different rates of chronic illness among African Americans, including lung disease, asthma, heart disease, cancer, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, along with the thousands of blacks with immune systems compromised by HIV. These chronic illnesses are comorbidities associated with COVID-19. Meanwhile, research on the social determinants of health shows that living in underdeveloped neighborhoods and residing in dilapidated, unaffordable houses produce toxic stressors, which spawn undesirable health outcomes. African Americans and people of color mostly and often populate these neighborhoods. In every city in the United States, you can find these undesirable spaces.

The location of blacks in low-income jobs, which placed them on the economic edge and clustered in frontline occupations where social distancing is impossible, is the reality that amplifies African American vulnerability to the virus. Blacks work in grocery stores, drive buses, and labor as health-care aides, retail, and other positions that make social interaction necessary. For example, in the Bronx, which is 84% black, Latinx, or mixed-race, these essential workers could not obey the “stay at home” orders, retorted Jumaane Williams, the New York City public advocate. He says these workers had to fend for themselves and go to work with little protection. Consequently, in the Bronx, there is still a rush hour.

Less than 20% of blacks can work remotely, out of harm way of COVID-19. Many of the remaining black laborers represent the essential workers mentioned by Williams. These workers are public transit-dependent and have no choice but to ride the crowded buses and subways, intermingling with the horde. These same workers, and other African Americans, live in overcrowded, multigenerational homes, where purchasing masks, gloves, hand sanitizers, and other COVID-19 protective gear is challenging. In this apocalyptic moment, one person’s necessity is still another person’s luxury. This reality is why Charles M. Blow, an opinion columnist for the New York Times, characterized social distance as an extravagance in the black community and branded COVID-19 as a ticking racial time bomb.

Pundits might need to educate the public about the issues, but it is old news to elected officials, public health experts, and urban planners. Yet, this knowledge was never translated into action, down on the ground, in black communities to blunt the devastation.

Systemic structural racism is the reason why.

When COVID-19 invaded the United States in January 2020, elected officials and public health experts portrayed it as an equal opportunity virus that would impact all people. The Philadelphia Health Commissioner Thomas Farley posited, “This virus does not discriminate. The virus is in every neighborhood. It’s in every population.”

The poster child for this “equal opportunity” narrative was affluent, metro New York’s New Rochelle, a predominantly white community, which was the early epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak in the Empire State. African Americans knew better. In the United States, disease has always discriminated, and black’s captured their knowledge of the resultant health disparities in the black proverb, “when white folk catch a cold, black folk get pneumonia.” Many diseases did not attack blacks because of their race, but because of their race-based vulnerabilities.

In Farley’s Philadelphia, for a moment, COVID-19 masqueraded as an “equal opportunity” virus. At first, most coronavirus patients were white, but that quickly changed. Now about 40% of the confirmed positive cases of COVID-19 are black, with whites accounting for only about 14%. The pattern is that those with the means to travel spread the virus, but once it invades a community, it seeks out the most vulnerable populations on which to prey. The St. Joseph’s University sociologist Maria Kefalas says, “one of the few constants in social science is that all illness impacts poor people more harshly”.

The government, elected officials, and public health officials ignored this social science constant, along with the high probability that COVID-19 was going to hit blacks with sledgehammer force. Alex M. Azar, the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, should have called for the collection and public reporting of data on race and ethnicity related to COVID-19, including data on testing, hospitalization, and mortality. Such information is vital to monitoring outbreaks, identifying disparities, and strategically responding to the needs of communities. The Secretary did nothing. Despite a groundswell of demands for such data, Secretary Azar has yet to act.

The Black U.S. Surgeon General, Jerome Michael Adams, could have pleaded with the Trump Administration to push for such statistics and to establish a national task force to forge proactive plans to protect the vulnerable African American population. Instead, Adams paternalistically scolded black people for not “stepping up.” Local health officials could have taken the lead by reporting data on race and ethnicity in their communities and by establishing task forces to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 in the African American community, but they disregarded the danger.

The failure of the Trump Administration and leadership at every level of government to forestall the COVID-19 assault on Black America did not result solely from malfeasance or ignorance. But, it came from the reality of our nation’s systemic structural racism. The devaluing of black life is the central component of structural racism. Angela Glover Blackwell and Michael McAfee of PolicyLink, a national research and action institute, characterized this aspect of structural racism as a hierarchy of human value, which places blacks at the bottom. Thus, when COVID-19 attacked the United States, the Trump Administration disregarded blacks, while rushing to construct a safety net for white business elites at the top of the human value ladder.

“ ‘IT IS VERY SAD,

BUT THERE IS

NOTHING WE CAN

DO RIGHT NOW

ABOUT BLACKS

AND COVID-19.’ ”

FOR CORPORATIONS

They studied the possible impact the economy would have on the private sector, especially the large corporations, the airline industry, the retail and tourist, and hospitality industries, along with the finance, home mortgage, and apartment industries. Knowing that millions of workers would be laid off and would not be able to pay mortgages or rents, mitigation strategies, however imperfect, were put together. The Trump Administration, and congressional leaders, forged a plan and translated it into action.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act generated a massive bailout for the private sector. CARES set up a $500 billion fund for loans to corporate America. All of the companies receiving these funds have business continuity plans designed to keep their firms operating during a disaster, such as the CONVID-19. These companies have the cash reserves and credit lines necessary to survive calamities. Corporate American, if necessary, could have endured without this loan fund, which the Democrats derided as a slush fund. The bipartisan Congressional Small Business Task Force carved out a 367 billion loan and grant package for small businesses for inclusion in the CARES Act while minimizing support to micro-level firms with less than 20 workers. Then, the Administration targeted 25 billion in “cash grants” to airlines (in addition to loans), $4 billion for air cargo carriers, $3 billion for airline contractors (caterers, etch) for payroll support.

The government also assisted homeowners and even helped the apartment industry mitigate the impact of folks not being able to pay rent by making mortgage forbearance possible. They did provide renters with foreclosure protection for 120 days but did not freeze rents during this period. Payments to landlords will be due after the four-month grace period.

The Trump Administration assisted those elite groups high on the human value ladder but did nothing to shield the black community for the ravages of the coronavirus. The arrogant disregard of the White House, and other public officials, is best illustrated by Dr. Anthony Fauci, the likable director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Fauci, standing next to President Donald Trump at a White House Briefing on April 7, 2020, said matter-of-factly, “It is very sad, but there is nothing we can do right now about blacks and COVID-19.

This staggering indifference, and admittance, to black life is what COVID-19 revealed. Blacks have had other shameful experiences in the United States, including the eugenics movement, the Tuskegee Experiment, known officially as the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male in the 1930s, the minimization of Black polio victims and the politics of medical segregation before World War II, the persistence of race-based health inequities, along with Hurricane Katrina, and the epidemic of police violence against Blacks. Yet, somehow these tragedies pale beside the COVID-19 pandemic that is wreaking havoc in black, brown, and immigrant communities. COVID-19 has snatched the covers off of color-blind racism, the inclusive rhetoric, along with the declining significance of race to reveal the racist fault lines in the structure of U.S. society.

COVID-19 also unveiled the interactive link between the deplorable conditions found in underdeveloped neighborhoods and black health vulnerabilities, including premature deaths. COVID-19 stalked African Americans not only because of chronic diseases but also because of their horrid living and working conditions made them easy prey. In Buffalo, New York, for example, 51% of all confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Buffalo, and 20% in Erie County, are found in just six census tracts, situated on the East Side, where blacks are concentrated. This overrepresentation confirms the relationship between the coronavirus and those underdeveloped neighborhoods, where black and brown people reside.

We suspect that a similar relationship exists between underdeveloped neighborhoods and COVID-19 in other cities. Chronic illness and health inequities are thus, problems that confront blacks because of their clustering in places characterized by limited services, decaying infrastructures, and inadequate housing. Most of the workers in such communities will be on the economic edge and hold jobs in essential occupations. These living conditions and income realities spawn Black vulnerability to COVID-19 and other diseases. They will persist, becoming increasingly complex and difficult to resolve, until eliminated.

There is, however, a silver lining to the dark cloud. Across the nation, voices of outrage are being raised in opposition to the black devastation wrought by COVID-19. Health practitioners, elected officials, community activists, and ordinary citizens are demanding action. The Princeton University professor, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, summed it up this way, “Public official lament the way that the coronavirus is engulfing black communities. The question is, what are they prepared to do about it?” The answer to the question is about more than reducing the impact of COVID-19 on blacks, it also requires fundamentally transforming the neighborhoods in which they live, and eliminating social determinants as the prime producer of undesirable health outcomes in Black life. It demands that urban planners, along with the American people, imagine another, very different, but a possible city, a place anchored by racial, economic, and social justice.

The University of Pennsylvania scholar and director of the Netter Center for Community Partnerships, along with his colleagues, said: “The world will never be the same again.” Harkavy and his colleagues argued that this “safe prediction” suggests that we have the opportunity to re-shape the world or slip back into the old systems of power and inequity.”

THE CHOICE IS OURS.

Author Profile

Latest entries

Gun Control06/18/2025Trump says the US knows where Iran’s Khamenei is hiding and urges Iran’s unconditional surrender

Gun Control06/18/2025Trump says the US knows where Iran’s Khamenei is hiding and urges Iran’s unconditional surrender Selected Media06/18/2025Israel-Iran live updates: Trump weighs U.S. strike as Iran’s supreme leader says the ‘battle begins’

Selected Media06/18/2025Israel-Iran live updates: Trump weighs U.S. strike as Iran’s supreme leader says the ‘battle begins’ Selected Media06/18/2025Federal judge on bench for 40 years lambasts grant terminations as ‘racist’ and anti-LGBTQ.

Selected Media06/18/2025Federal judge on bench for 40 years lambasts grant terminations as ‘racist’ and anti-LGBTQ. Selected Media06/17/2025US president’s comments come after he warns Tehran residents to leave ‘immediately’.

Selected Media06/17/2025US president’s comments come after he warns Tehran residents to leave ‘immediately’.