By Stephen T. Watson

Reposted from Buffalo News

July 19, 2020

Millard Fillmore gets little love from presidential historians, but he’s enjoyed favorite son status in Buffalo for more than 150 years.

That’s beginning to change.

The 13th president lived here for years before and after his term in the White House. His fingerprints are on many educational and cultural institutions, from the University at Buffalo to Buffalo General Medical Center, and his name and image are sprinkled throughout greater Buffalo.

Now, Fillmore’s signing of the Compromise of 1850 – which included the loathsome Fugitive Slave Act – and his unsuccessful presidential run as a member of the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic Know Nothing Party are raising questions about his lofty local status.

In response, the City of Buffalo, UB and Kaleida Health all are pledging to review statues, building names and other ways Fillmore is honored locally – with the revaluations conducted by the city and the university part of broader assessments that include other historic figures.

“What’s named after Fillmore does matter, because it can send a chilling message to members of the community,” said Robert Silverman, a UB professor of urban and regional planning who has publicly urged the university to stop honoring Fillmore.

This Fillmore reconsideration is part of a historic reckoning that has touched Christopher Columbus, Woodrow Wilson and numerous other figures and symbols from the past.

Statues and building names honoring presidents, explorers and generals, among others, are coming down as their records receive a closer look.

Proponents of this historic reassessment say America for too long has built statues to racists, Confederate traitors and leaders who massacred Native Americans. They say it is well past time, instead, to honor accomplished women and people of color.

Historians say it is important to put Fillmore and other figures in the context of their times and to educate people on the person in full.

But is it possible to recognize people for their accomplishments while simultaneously pointing out their least appealing characteristics? And is it realistic to hold a figure from another century to modern standards?

“It’s absolutely not fair. You can’t judge what happened 200 years ago by your values today,” said Kathy Frost, curator of the Millard Fillmore Presidential Site, the East Aurora home where Fillmore began his legal and political careers.

Buffalo’s president

Fillmore was born in 1800 in the Finger Lakes. He grew up in poverty and had little formal schooling before he moved to this area, initially as a teacher until studying to become a lawyer.

He built a house on Main Street in East Aurora in 1826 for his new bride, Abigail, and opened a legal practice. The Fillmores lived there for about four years before moving to what is now downtown Buffalo.

Fillmore rose rapidly through the political ranks, serving in the state Assembly and in Congress and as state comptroller before becoming vice president under Zachary Taylor in 1849.

He took over as president in July 1850 upon Taylor’s sudden death. He finished the rest of Taylor’s term as president but was not nominated by his fellow Whigs for reelection in 1852. Fillmore returned to Buffalo after his presidential service and died here in 1874.

Coward or pragmatist?

Outside Buffalo, Fillmore largely is considered one of the country’s worst presidents.

That’s partly, Frost said, because he served less than one term, he was an accidental president who never won office on his own and he never gave an inaugural address outlining a broad vision.

“He’s an unknown president,” the presidential site curator said.

His accomplishments as president include opening – through “gunship diplomacy” – the port of Japan. But slavery was the central point of debate in the country at the time, and it is on this issue that Fillmore’s legacy doesn’t hold up well to scrutiny.

Advocates who sought to maintain slavery wrangled with abolitionists who wanted to put an end to it.

That led to the Compromise of 1850. Its most notorious element was the Fugitive Slave Act, a law requiring the return to their owners of any slave – even those found in a free state – and obligating the federal government to participate in this system.

It was negotiated while Fillmore was vice president but he signed it upon taking Taylor’s place, though Fillmore professed to personally oppose slavery.

“In his eyes, though, he was trying to keep the Union together. He was trying to obey the Constitution. He was trying to avoid the impending Civil War,” said Anthony Greco, the Buffalo History Museum’s director of exhibits and interpretive planning, adding, “Nowadays, we would see his actions or inaction as cowardly – or maybe self-preserving.”

Fillmore’s local legacy

Here, however, Fillmore is remembered more for his contributions to the community than for what he did as president.

Fillmore was the founding chancellor of UB. And as the city was growing in the early and mid-19th century, Fillmore played a role in establishing many institutions that live on today: the Buffalo Club, the Buffalo Museum of Science, the public library, the History Museum and what is now the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo General Medical Center and the local chapter of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

In some cases, Fillmore wasn’t a hands-on founder but someone organizers sought to bring him on board because his involvement lent prestige.

But Fillmore genuinely was invested in his adopted hometown, Frost said. “We call him the first citizen of Buffalo,” she said.

In turn, monuments to Fillmore abound in this area.

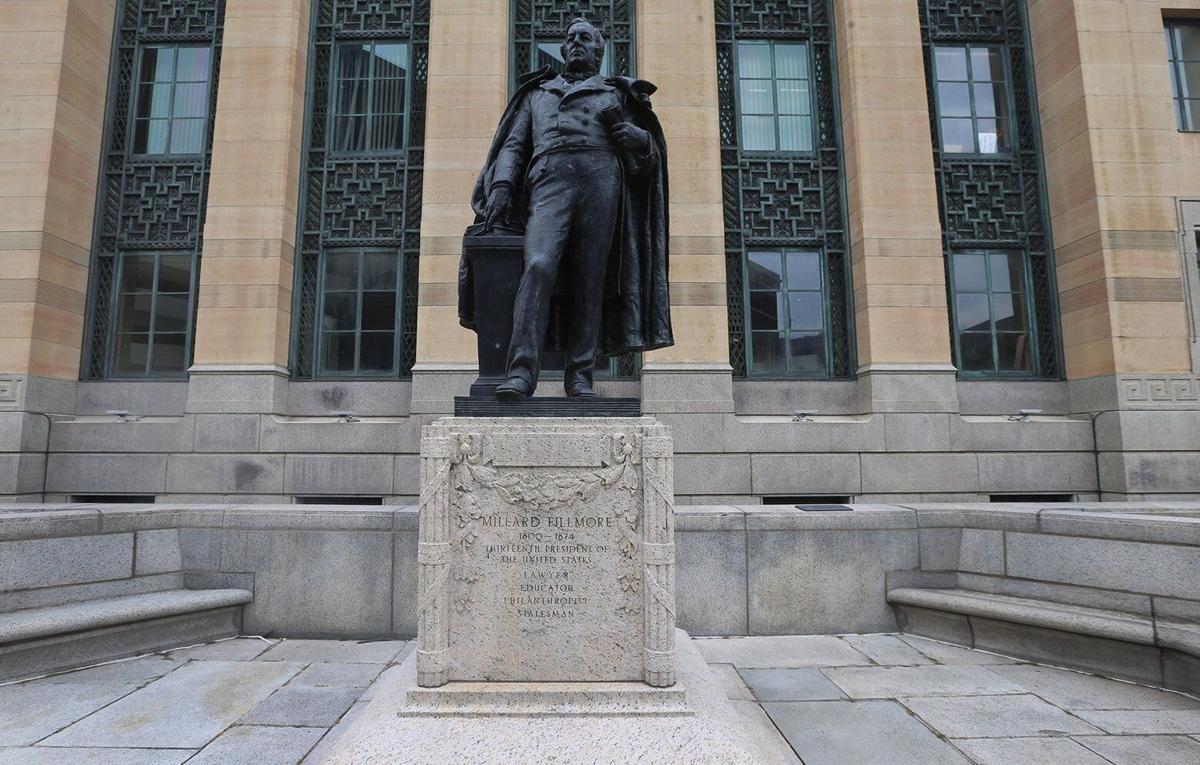

His statue stands outside City Hall – along with a statue for Buffalo’s other president, Grover Cleveland. And Fillmore Avenue and the Fillmore District in Buffalo both are named for the former president.

At one point, two area hospitals, Millard Fillmore Gates Circle and Millard Fillmore Suburban Hospital, bore his name.

His former East Aurora residence is a National Historic Landmark, moved off Main Street and restored as best as possible to its 1820s appearance.

“Most of our guests are presidential enthusiasts,” Frost said.

The History Museum has in its collection an original Fillmore carriage, the charcoal sketch used as the basis for Fillmore’s official White House portrait, an inkwell and two bottles of Madeira wine given to Fillmore after Commodore Matthew Perry returned from his Japanese expedition.

“We don’t celebrate him here,” Greco said. “We acknowledge him. We mention the good with the bad. We shine a light on the bad things he did. We also give credit where credit is due. The summary we say is: terrible president, again, good Buffalonian.”

The whole story

Rethinking Fillmore’s place of honor in Buffalo isn’t a new idea.

The Buffalo chapter of the NAACP in 2015 asked the Common Council to stop naming things for Fillmore.

“We are not asking for anything to be removed, but for the full historic picture to be presented,” the late Frank Mesiah, the longtime chapter president, said then. “He was the president. Tell that he was the president. But also tell that he helped maintain slavery.”

And members of the UB community over the years have raised concerns about Fillmore, whose name for decades was on the university’s continuing education program before it was folded into other academic units.

UB officials also organized an annual ceremony at Fillmore’s gravesite in Forest Lawn on his Jan. 7 birthday. Silverman, the UB professor, objected to the use of university resources for this event.

“It is time for UB and the City of Buffalo to stop equivocating about Millard Fillmore, take action and take a stand against racism and xenophobia,” Silverman wrote to the Spectrum student newspaper this month in a letter that also called for the removal of the City Hall statue.

Members of the UB Black Council earlier this month sent their own letter to the Spectrum with a list of demands to improve the experience for Black students on campus, including requesting the university rename the Millard Fillmore Academic Center in the Ellicott Complex.

It isn’t just Fillmore facing a reckoning.

A local Italian American society asked the City of Buffalo to remove Columbus’ statue from Columbus Park, which also will be renamed. Historians say the explorer committed acts of genocide against the native people he encountered in the Americas.

Princeton University has removed Woodrow Wilson’s name from its public policy school and one of its residential colleges. Wilson was known for his racist views and policies, including resegregating the federal workforce.

Numerous Confederate statues and memorials have come down and Mississippi lawmakers agreed to remove the rebel symbol from the state’s flag.

In Buffalo, Mayor Byron W. Brown is asking the city’s Arts Commission to reexamine all of the city’s statues and monuments with assistance from History Museum staff.

“I have asked that this review be done in the context of the time the person lived in and weighing their entire record,” Brown said in a statement to The Buffalo News .

Brown said he also wants more recognition for women, Blacks, Latinos, Native Americans and others whose stories too often go untold. As an example, Brown said he favors a statue of Mary B. Talbert, the suffragist, writer and reformer who lived in Buffalo and was a founder of the precursor organization to the NAACP.

“Talbert was an international icon and one of the best-known African Americans and women of her time,” Brown said.

At UB, spokesman John DellaContrada said the university stopped co-sponsoring the annual Fillmore birthday ceremony this year because of concerns raised about his presidential legacy.

He said a committee is continuing to review the names on campus buildings and roadways, including the Fillmore academic center.

“UB’s examination of these issues is essential as we build on our commitment to explore, understand and respond to racism and systemic inequality and dismantle barriers to equity and inclusion,” a UB statement reads.

Kaleida Health said officials renamed the Buffalo Homeopathic Hospital in honor of the former president in 1923. The suburban location opened as an extension of the Gates Circle hospital, now closed and torn down, in 1974.

The hospital system said the name honors Fillmore’s role in 1858 in founding Buffalo General Hospital and is not an endorsement of his presidential policies.

Spokesman Michael Hughes said no one has previously raised a concern about the Millard Fillmore name with Kaleida Health officials. However, he said system employees who address issues of diversity and inclusion within the hospital network will study and address the issue.

“It is important that we continue to respect and embrace our diverse community, which will only help us provide better service and care for our patients,” Hughes said in a statement.

The Fillmore debate isn’t going away, and it is on full display at the History Museum, where a relief sculpture was carved into the building’s exterior.

“He’s literally emblazoned on the outside of our building, so he’s not someone we can run away from,” Greco said.