Police the Public, or Protect It? For a U.S. in Crisis, Hard Lessons From Other Countries

Read the full article from New York Times, here.

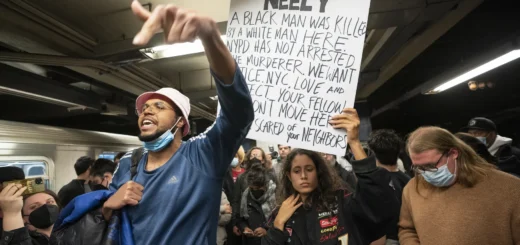

“No justice, no peace. No racist police!”

Weeks of nationwide demonstrations, in which that chanted demand has echoed in streets across the United States, have made one thing clear: The American police face a crisis of legitimacy. And its consequences reach far beyond policing itself.

Those intent on remaking law enforcement to redress decades of racial injustice would do well to look at the experiences of other countries that have wrestled with just that challenge. So would those who insist that there is no problem to be fixed.

Author Profile

Latest entries

Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.01/20/2025Reflections on Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Dream

Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.01/20/2025Reflections on Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Dream Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.01/09/2025The Trump Inaugural Parade is a Political Event

Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.01/09/2025The Trump Inaugural Parade is a Political Event Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.05/04/2024The Occupation of Hayes Hall: Student Rebellions and Remaking the U.S. UniversityThe Occupation of Hayes Hall

Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.05/04/2024The Occupation of Hayes Hall: Student Rebellions and Remaking the U.S. UniversityThe Occupation of Hayes Hall Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.03/21/2024Ryan’s infill housing strategy is the right plan for Buffalo

Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.03/21/2024Ryan’s infill housing strategy is the right plan for Buffalo