Baton Rouge: A Divided City

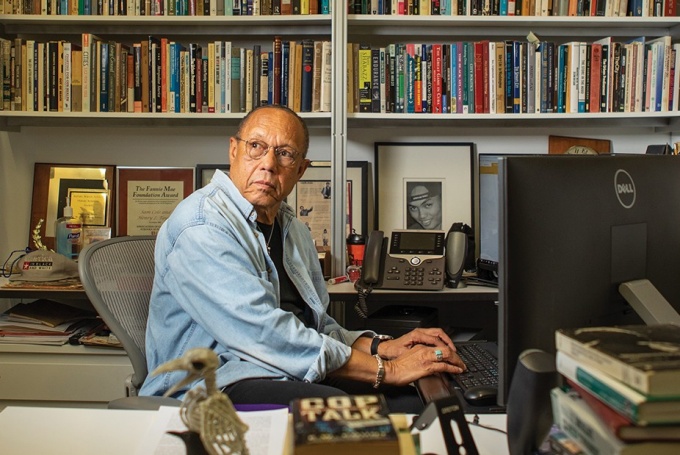

Professor at Louisiana State University

No, Baton Rouge is not burning. Baton Rouge is a city divided by many fault lines. A single street divides the city’s predominately white and black communities. North Baton Rouge, where Alton Sterling was killed, is under developed relative to south Baton Rouge. Access to emergency rooms, quality schools, healthy food, reliable transportation, and good jobs are limited, while health care complexes, blue ribbon schools, business and industry flow freely to the south. With the exception of a small section of Gardere in south Baton Rouge, which is predominately black, the sight of strong law enforcement presence is hard to find. Conversely, in several zip codes in north Baton Rouge, there is a noticeable police presence. Programs aimed at addressing homicides and violent crimes in predominately black areas are welcomed sites for many members of the dominant racial group but for some blacks in the city and for others the program is viewed as doing more harm than good. Such programs whether intentionally or unintentionally stigmatize both people and place and further increase the gap between blacks and whites who despite some claims have not forgotten the city’s tremulous racial past.

When whites talk about “the university” they are referring to Louisiana State University, while blacks refer to their beloved Southern University, a Historically Black College and University. For a time blacks had few educational opportunities as they were excluded from many public and private schools, colleges, and universities in the city.

Earlier this year I served as co-chair of a commemoration committee with Raymond A. Jetson, Pastor of Star Hill Church located near the site of Sterling’s killing, honoring men and women for their role in the nation’s first bus boycott in 1953. On the same day of the ceremony revelers were in the Spanish Town neighborhood riding on and watching floats as part of annual Mardi Gras festivities. Floats mocking the nation’s first black president, Black Lives Matters, victims of police brutality, among other offenses, were paraded down city streets. Some city residents could not understand why such public displays were viewed as offensive and accused critics of being overly sensitive and bowing to so-called political correctness. A tale of two cities is what we have in Baton Rouge and it is what has always existed.

For those unwilling to believe Baton Rouge was and is a city divided they need only view the Frontline documentary about the effort on the part of a large group of whites living in unincorporated municipalities in south Baton Rouge to secede from the city. While the stated purpose for the creation of the City of St. George, at least in part, was to have access to high-quality schools for area children, it was clear the new city would not resemble the existing city in terms of racial or economic composition.

In the weeks leading up to the shooting of Alton Sterling, the city was debating whether a school in 2016, in the city’s predominately white section should still carry the name of a legend of the Confederacy, Robert E. Lee. The district voted to drop Robert E. from the title, but the school remains named Lee High School.

Controversial dress codes at establishments serving local college students on the city’s south side, which appeared to target young men of color, and the defense of such codes, also revealed the very different worlds blacks and whites in Baton Rouge occupy.

This is just a small window into some of the events leading up to the killing of Alton Sterling and the demonstrations that followed. The daily experiences of people of color from every end of the economic and educational spectrum are too numerous to list here. As a college professor and as someone actively engaged in community-based efforts to improve the quality of life for all residents, especially residents from historically disadvantaged groups, I get to see and hear what by colleagues, students, and neighbors must endure. It is therefore not surprising that many people, particularly many people of color, are concerned about transparency, fairness, and sometimes question “official” accounts.

No, Baton Rouge is not Ferguson, but Baton Rouge is a city in this nation like many others with a long history of treating people differently based upon the racial groups to which they belong. The entire nation is suffering and witnessing the consequences of a racialized social structure, which was in place before any of us were born and which far too few people are willing to challenge. It is a racialized social system, which privileges some and disadvantages other by race. It allows some people of privilege and positions of power and influence to look with distain on the oppressed all the while celebrating the oppressors.

Our failures to adequately confront racism in a way that will truly transform communities and the nation have brought us to this place in time. It has brought us to a place where I fear for the physical and emotional well-bring of my students and fellow citizens committed to social justice issues.

My students who are also veterans describe participating in a peaceful protest with a show of force reminiscent of their time in Iraq. My students and others report looking down the barrel of a gun, armored vehicles in sight, being thrown to the ground, and sitting in the back of police vehicles unsure of their offense, and worried about their future. Others report coming to the aid of small children in distress as their parents and siblings, who contend they were peacefully protesting, were detained.

Race matters. Race is not declining in significance. So many of us have been saying this for years. Knowing and understanding history is a double-edged sword. Understanding what is happening in Baton Rouge and throughout the nation is a blessing and a burden. On the one hand, I can provide context for what is happening to others finding the last few days events hard to wrap their mind around. On the other hand, I can be confident what is happening in Baton Rouge is likely to happen again, here or in some other place. Sadly, civil rights are bestowed upon some at birth, while others have to fight tooth and nail for basic human rights.

Increasingly, many are asked to “stay woke.” Many of us have “been woke” for a long time and with the killings in Baton Rouge, Minnesota, and Dallas, now some people are beginning to hear the alarms. The future of race relations in the City of Baton Rouge and in the nation depends on many more people not merely hearing but responding to the alarms in a way that results in a more just and more equitable society. Mocking, dismissing, or diminishing the misery experienced by others are not viable solutions and will not move us forward.

Author Profile

Latest entries

Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.01/20/2025Reflections on Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Dream

Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.01/20/2025Reflections on Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Dream Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.01/09/2025The Trump Inaugural Parade is a Political Event

Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.01/09/2025The Trump Inaugural Parade is a Political Event Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.05/04/2024The Occupation of Hayes Hall: Student Rebellions and Remaking the U.S. UniversityThe Occupation of Hayes Hall

Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.05/04/2024The Occupation of Hayes Hall: Student Rebellions and Remaking the U.S. UniversityThe Occupation of Hayes Hall Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.03/21/2024Ryan’s infill housing strategy is the right plan for Buffalo

Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.03/21/2024Ryan’s infill housing strategy is the right plan for Buffalo